Nature Trail Part 3: Mud Flats

Mud Flats, Cradle of Life

Habitat

Every animal species has unique needs that must be offered by its habitat. Biologists commonly refer to such needs as “habitat requisites“. Key requisites required for species survival are food, water, cover, and space. If anyone of the Key features of a specific habitat is missing/ stressed, the habitat quality decreases. There are a number of habitat types defining the ecology of an estuary. Main inter-tidal habitat types associated with the Cowichan-Koksilah Estuary include:

sea bottom (mud, sand, gravel);

eelgrass beds;

mud flats;

salt marshes;

beaches (sand, gravel, cobble, bedrock, boulders)

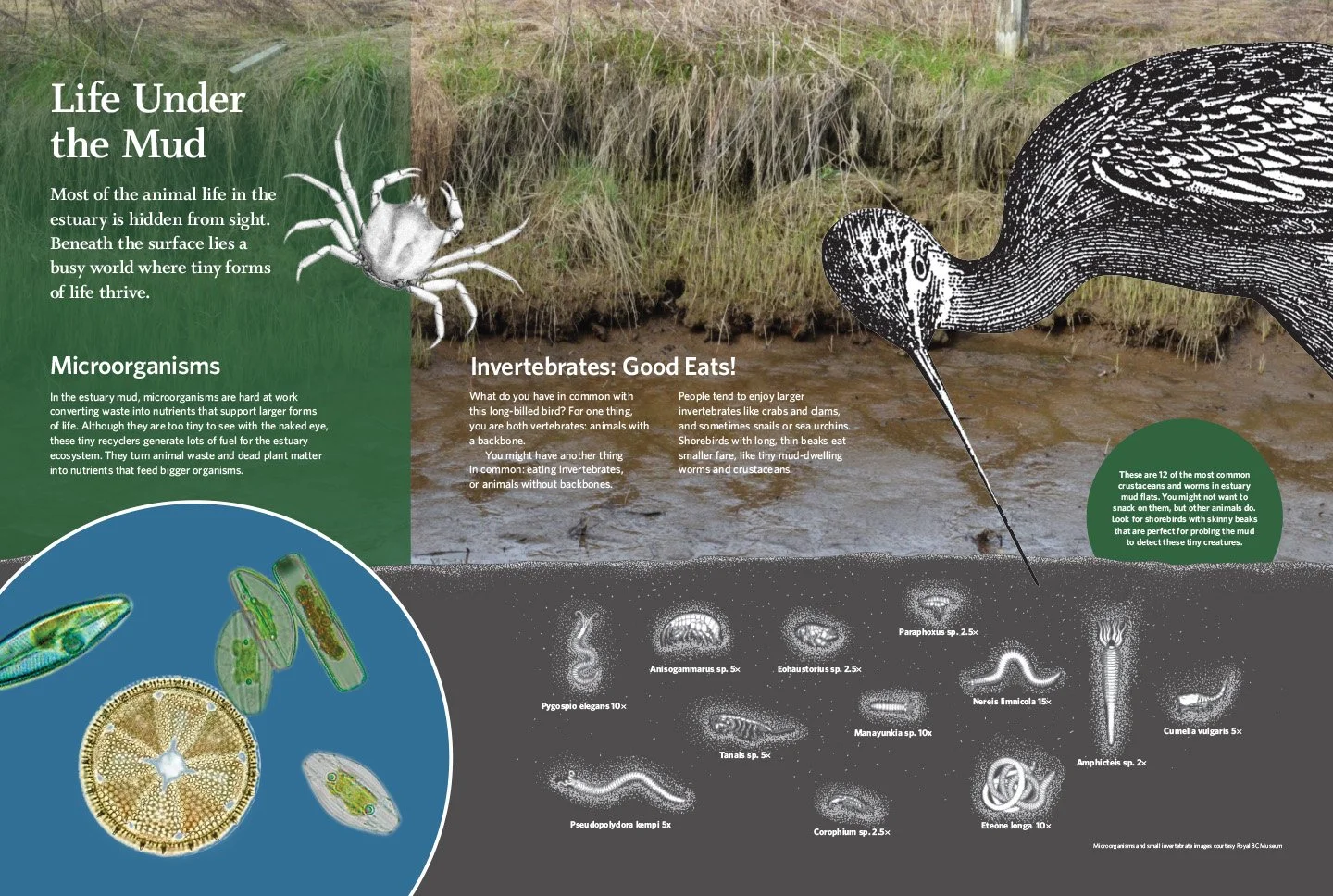

This trail sign explains the role of microorganisms and invertebrates typical for the Cowichan-Koksilah mud flats.Together with the mixing of salt- and fresh water in an estuary is the mixing of sediments from the rivers and from the sea. A mixture of very fine silts from tidal waters and alluvium from rivers dropping their load as they reach the sea is deposited, causing a build up of mud layers, referred to as mud flats. Mud flats are typically found in areas where the tidal waters flow slowly.Mud flats are covered at high tide and exposed as the tide drops. At low tide the intertidal mud is exposed as a mud flat leaving water only in permanent channels. At high tide the mud flats are covered by salt- and brackish water.A main habitat such as a mud flat may be stratified into “sub-habitat types“, also called micro-habitat. These are smaller units that display visually recognizable homogeneous components providing specific features favourable to one single species or a species group.

Cowichan-Koksilah Mud Flats

In the Cowichan-Koksilah Estuary mudflats constitute size-wise the main habitat type. Here the mudflats are located between the open sea and vegetated salt-marshes. This intertidal habitat contains a high organic content originating typically from the salt-marshes, phytoplankton developing at low tide through photosynthesis, to a lesser extent from sub-tidal eelgrass beds, and organic materials carried onto the mud-flats by its tributaries. The mud flat is crisscrossed by winding channels that are kept open by tidal action. Unless these channels are fed by active water sources (i.e. North-and South Forks of the Cowichan and Koksilah Rivers), they will usually dry out at low tide and contain no water as increasingly noticeable during the past dry summers when both rivers started to dry up.

The mud flats of the Cowichan-Koksilah Estuary can be stratified into several micro-habitats; the largest being composed of pure mud, others are formed by alluvial materials composed of gravel and pebbles mixed with clay and silt flushed into the estuary by the Cowichan River during typical fall and spring floods. Micro-habitats therefore develop mostly next to active drainage channels where banks and berms are built up over time and along shorelines. This adds to the biophysical diversity of the estuarine ecosystems as reflected by the distinctive groups of animal species found in such micro-habitats that offer requisites not found in pure mud.

How do we benefit from mud flats?The shallow mudflats dissipate wave energy, thus reducing the risk of eroding salt-marshes and flooding low-lying land. The mud surface also plays an important role in nutrient chemistry.It is known that in estuaries receiving pollution, organic sediments sequester contaminants and may contain high concentrations of heavy metals as also has been the case in the Cowichan Estuary.The capacity of mudflats to sequester carbon much more efficiently than boreal forests is becoming of increasing importance in the light of global warming, the main cause of climate change. The carbon sequestered by estuaries commonly referred to as 'blue carbon' will be subject to another article of this nature trail series.One of the more tangible benefits of healthy mud flats is the rich supply of shellfish, a staple food that has been utilized by Cowichan Tribes for centuries until the man-caused shellfish closure came into effect almost 40 years ago.Mud flats are highly productive areas which, together with other intertidal habitats, support large numbers of birds and fish. They also provide feeding and staging areas for internationally important migrant and wintering waterfowl, and are critical nursery areas for flatfish and shellfish.Impressive ProductivityMud flats are teeming with life. They are characterized by a high biological productivity and abundance of organisms, but low species diversity. The main food source in the estuarine-mudflat ecosystem is the large quantity of organic material (detritus). As mentioned previously this material originates mostly from marsh plants flourishing in the spring and summer and decaying in fall and winter when the dead plant matter is distributed within the same marsh or into mudflats where they become the first level of the food chain.Another important but sadly under-estimated source of organic material substantially contributing to the build-up of 'mud' are algae which start to grow when the tidal flats are exposed to air and sun (photosynthesis) with out-going tides.

It is like a miracle to observe the greening- up of mud flats at low tide when mostly mono-cellular algae (diatoms and euglenoids) start to grow with the help of the sun's energy. These algae form dense mats contributing to the stabilization of sediments which are bound together by mucilage, a viscous or gelatinous solution produced from plant roots, seeds and other plant material. Together these surface materials build the "biofilm" so typical for mudflats. The biofilm is a thin layer of organic material less than 4 cm thick mixed with silt hosting millions of live organisms which form the basis of the estuarine food-chain. Under nutrient-rich conditions, there may be mats of macro-algae such as Enteromorpha spp. or Ulva spp. (i.e. sea lettuce species) characterizing parts of the Cowichan-Koksilah Estuary.Microscopic organisms like bacteria, small algae, and fungi help to decompose the detritus resulting from the various sources. These microorganisms and the remaining decomposing plant material become an ideal source of food for bottom-dwellers in mudflats and salt marshes like worms, fish, crabs, and shrimps. Primary consumers, also called 'first-level consumers' (species feeding on plants), either living on or burrowing in the mud, feed on these organic materials. Examples of these are barnacles, mussels, oysters, polychaetes and oligochaetes (marine worms), burrowing molluscs and other zooplanktons. Attracted to these numerous and diverse populations are secondary consumers such as shore birds, fish and invertebrate predators like crabs, shrimps and carnivorous marine worms. As with many food webs, microorganisms at the most primary level on the food chain are responsible for more than one role. The same microorganisms feeding on detritus cover the mud surface, stabilize sediments, feed larger animals, and add nutrients to the sediments.

§ In-filling and dyking: causing massive disturbances in Cowichan Bay mudflats (examples: Westcan Terminal and Causeway, Western Forest Products Mill site etc.).

§ Estuarine dynamics: mudflats deposited in the past may erode due to changed estuarine dynamics (e.g., Causeway in Cowichan Bay).

§ Land claim: for urban, transport, and industrial infrastructure.

§ Barrage schemes: water storage, and flood defence (dyking) continue to pose a threat to the integrity and ecological value of mudflats in estuaries.

§ Diffuse and point source discharges from agriculture, industry, and urban areas: including polluted storm-water run-off, can create abiotic areas or produce algal mats which may affect invertebrate communities; they can also remove embedded fauna and destabilising sediments thus making them liable to erode; they also may contaminate estuarine habitat causing a human health hazard (e.g. coli bacteria in Cowichan Bay causing shellfish closure) and a threat to estuarine life.

§ Freshwater shortages: mostly in the summer increase salinity of mud-flats affecting organisms depending on brackish water (e.g., 2015 and 2016 extended drought causing severe freshwater shortages in the rivers and Cowichan- Koksilah Estuary).

§ Invasive species or non-native species: for example the spread of cord-grass Spartina anglica vegetating some upper-shore mudflat areas with important ecological consequences.

§ Higher sea level and increased storm frequency: resulting from climate change may further affect the sedimentation patterns of mudflats and estuaries.

§ Sea level rise: low water moves landward, but sea defences prevent a compensating landward migration of high water mark with the result that intertidal flats are squeezed out. Much of this loss can be expected in estuaries such as the Cowichan-Koksilah.

§ Log and woody debris accumulation: research on forage fish has established the severity of the damage that is occurring due to log accumulation and scouring in the estuary. This is specifically damaging to forage fish habitat along the shorelines critical for spawning and rearing. Surf smelt and sand lance spawn and rear in gravel and sand beach habitats in the upper one third of the intertidal zone. Many species of salmon, marine mammals and sea birds depend on forage fish.

Dredging for navigation and log-boom transport have an important effect on sediment biota, sediment supply and transport; they are believed to be mostly responsible for the disappearance of eelgrass in the Cowichan-Koksilah Estuary.

In summary, estuarine mud flats as one of the ecologically most important macro-habitats of estuaries have to be protected for all reasons described above. Mudflats of the Cowichan Estuary continue to suffer from severe impacts mostly caused by inter-tidal log-boom storage and movement and large accumulation of woody debris (i.e., bark from log booms).