Nature Trail Part 2: Salt Marsh Habitat

Cowichan Estuary Nature Trail – Open Air Classroom Series Part 2:

Salt Marsh Habitat

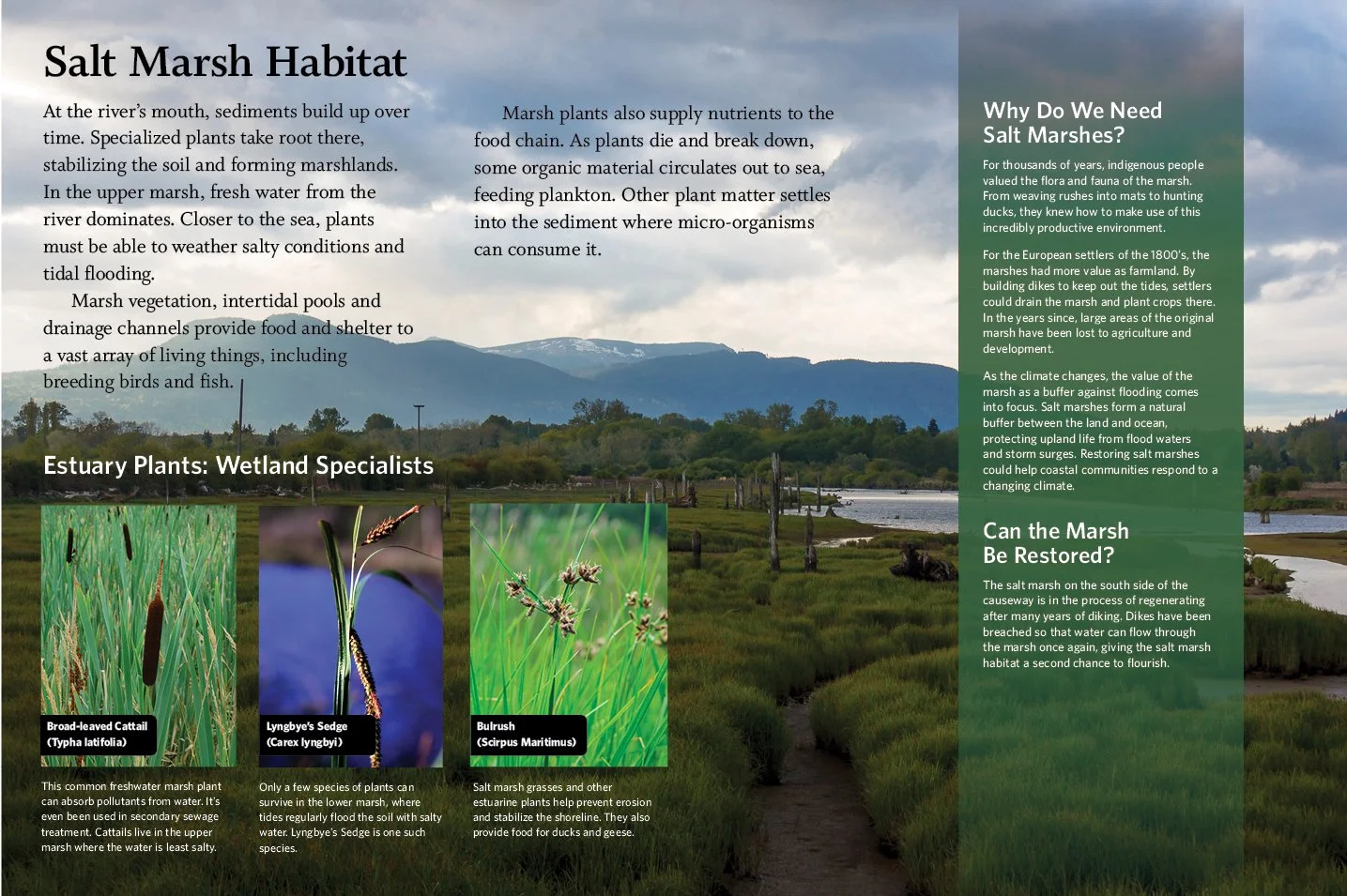

This is the first interpretative theme sign along the nature trail. Its strategic location allows the visitor to study on site what is shown by the sign's background photo: a healthy salt marsh to the north of the trail traversed by a tidal runnel connected to the South Fork of the Cowichan River.

Although the ecological importance of salt marshes and main sources of disturbances and threats are aptly summarized by the sign it appears prudent for a better appreciation to provide more detail on the complexity of this key habitat.

Evolution of Salt Marshes

Salt marshes are formed by 'succession' (Stage 1). A succession is defined as the serial development of different vegetation types at a place over time. This complex process starts with the growth of unicellular algae gluing the sandy material of the estuary together by production of mucus forming a brownish biofilm. Stage 2 is characterized by the growth of 'filamentous' algae (mostly blue-green algae) forming mats composed of long threads or 'filaments' which enable sediments to be stabilized by being caught in the web (filamentous algae are the prime food source for small gastropods). Stages 1 and 2 provide the conditions for the settlement of salt tolerant (halophytic) flowering plants (e.g. species in the family of Amaranthaceae). Germination of such species however is only possible after some desalination of the soil by rain and flood water from estuary tributaries.

Once established and properly anchored in the ground these salt tolerant plants enable sediment accumulation around their stems and root system slowly elevating and stabilizing the substrate (Stage 3).

This allows other plant species to develop and decompose, forming layer after layer of substrate in the process, eventually leading to the formation of a typical salt marsh, flooded and drained by tidal salt water and constituting the climax stage of a completed succession.

Since all plants are freshwater species, salt marsh vegetation has developed highly sophisticated mechanisms for species to survive under salty conditions, especially plant species in the earliest stages of succession. Suffice it to say that the ability for plants to adapt to such adverse environmental conditions is extraordinary. To explain the diverse and highly complex adaptation strategies of salt-resistant plants in detail goes beyond the scope of this salt-marsh overview. However it would be well worth it to read up upon this phenomenon as another example of miraculous evolutionary processes.

Salt marshes are generally ‘marshy’ because the soil is composed mostly of mud and peat. Peat is formed by decomposing plant matter. It is spongy, frequently water-logged, and low in oxygen levels. The latter, a condition referred to as ‘hypoxia’, is caused by the growth of bacteria producing the familiar sulfurous smell of rotten eggs in mudflats and salt marshes.

Functions of Salt Marshes

Salt marshes provide prime habitat for a large diversity of organisms ranging from micro-organism to macro-fauna. Salt marshes and mudflats are considered the cradle of life and the nursery of the sea. Marine life in salt marshes is highly diverse and abundant. Salt marsh species rely on the decay of marsh plants to supply a steady source of food in the form organic material, or detritus, resulting from the decomposition of plants and animals. The leaves, stems, and roots of salt marsh plants offer a vital shelter from predators and nourishment for young fish, shrimps, and crabs thriving in the network of runnels and inter-tidal pools of the marshland. Most marsh plants flourish in the spring and summer. In the fall, they begin to decay and are distributed within the same marsh or into mudflats where they become the first level of the food chain. Microscopic organisms like bacteria, small algae, and fungi help decompose the detritus resulting from salt marsh plants. These microorganisms and the remaining decomposing plant material become an ideal source of food for bottom-dwellers in salt marshes like worms, fish, crabs, and shrimps. The cycle continues when the feces of the bottom-dwellers is cleaned up by microorganisms. Anything left over is great fertilizer for the next spring, when the marsh plants fill the marsh with green lush leaves.

Salt marshes are essential for healthy fisheries, coastlines, and communities—and they are an integral part of our economy and culture. They also provide essential food, refuge, or nursery habitat for more than 75 percent of fisheries species, including shrimp, crab, and many finfish. They protect shorelines from erosion by buffering wave action and trapping sediments. They reduce flooding by slowing and absorbing rainwater and protect water quality by filtering runoff, and by metabolizing excess nutrients. The ability to re-charge groundwater is a function of increasing importance of spongy salt marshes.

Salt marshes are home to many species of birds providing nesting opportunities and food sources such as seeds, insects, fish, and shrimps etc. They are important breeding, feeding and overwintering grounds for waterfowl.

One of the fringe benefits of the ‘anaerobic’ (=deprived of free oxygen) conditions of salt marshes and mudflats is the ability to permanently store carbon produced within the de-composition process of dead plant material buried year after year, commonly referred to as ‘Blue Carbon”. Due to its increasing importance in the face of climate change the blue carbon issue will be subject to another part of this open-air classroom series.

Threats to Salt Marshes

The total number and area of salt marshes in the Cowichan Estuary -as in most estuaries and coastal areas of the world- has been declining for many decades. The main cause of salt marsh disappearance has been “enclosure” signifying removal of an area from tidal inundation by constructing a barrier to keep the sea out. The following map shows the extent of past dyking and infilling in the Cowichan estuary where numerous salt marshes had been converted for agriculture and grazing since the arrival of white settlers in the Cowichan Valley in the 1860s.

Urbanization, industrial development, effects from log transport and handling, pollution and modification of water flow through ditching and dyking as well as an invasion of alien species have contributed to the disappearance and degradation of the Cowichan Estuary salt marshes. Runoff containing industrial waste, pesticides and fertilizers pollute the marshes, leading to loss of species and the increase of others upsetting the ecological balance and integrity of the few remaining intact salt marshes.

Carol Hartwig, a CERCA member and active birder, reports that:

“Shorebird abundance and a number of other species groups such as Grebes, and some duck species in the Cowichan Estuary today is minimal compared to the past. These findings have been confirmed by recent citizen science surveys (BC Coastal Bird Survey Dec. 2012- Jan. 2014) and surveys and observations by local ornithologists who have made weekly observations for over 40 years. Observations of shorebirds such as Western Sandpiper, Least Sandpiper, Dunlin, Semipalmated Plover, Greater Yellowlegs, Pectoral Sandpiper, Short-billed Dowitcher, Long-billed Dowitcher, have become significantly less frequent or nil in many cases. Some of these populations are affected by environmental issues in other areas or continents but many of them are simply unable to find suitable habitats or forage that they did have in the past in the Cowichan Estuary. The declines of these shorebirds, grebes and some duck species can be connected to some degree (depending on the species and a number of other factors) to habitat loss, degradation, and alteration as a result of years of in-estuary industrial use and development particularly dredging channels for log transport and log booming and the resulting scouring of the estuary floor, accumulations of stray logs and bark in the estuary and salt marshes.”

Salt Marsh Rehabilitation

Expert consensus suggests that the Cowichan Estuary constitutes one of BC’s estuaries with the greatest potential for re-habilitation after almost half of it had been adversely affected by man-made causes. Within the past three decades Ducks Unlimited and the Nature Trust of BC have done a stellar job in purchasing privately owned alienated salt marshes of the estuary in an effort to rehabilitate their integrity.

In 2015 CERCA has joined these initiatives through re-habilitating one of the key salt marshes of the estuary located on Mariners Island. This project, financially supported by the DFO and Western Forest Products, was implemented by CERCA in cooperation with Ducks Unlimited, Cowichan Tribes and Western Forest Products.

The project focused on the removal of logs and woody debris washed up over time onto the marshes located to the south of the WFP mill pond in the heart of the Cowichan estuary. Prior to log removal by the CERCA project a large section of these highly productive marshes had been covered by a solid layer of logs in different stages of decomposition releasing CO2 in the process and destroying valuable wildlife habitat. As a result of the highly successful clean-up approximately 15 hectares of prime salt marsh interspersed with inter-tidal pools and water channels have been re-habilitated. More than 10 000 logs and large woody debris were removed from the island in the process.

The vegetation recovery after log removal has been remarkable reflecting the resilience of ecosystems. It now provides again food and shelter to a wide spectrum of fauna including a diverse avifauna and Chinook, Coho and chum smolt thriving along some of the still undisturbed sections of the island’s shoreline and the numerous inter-tidal pools and runnels typifying this important habitat. For further information on the amazing recovery of Mariners Island salt marsh it is referred to an earlier CERCA blog on our website June 10, 2016 entitled” ” Amazing Ecosystem Resilience “

The restoration also significantly enhances the carbon sequestration capacity of this salt marsh recognized as one of the most effective carbon sinks of all ecosystems.

The rehabilitated habitat includes mud, silt, sand and pebble surfaces along the shoreline, and grass/herb/shrub communities of the marsh land. It now allows recovery of forage fish populations, also benefiting migratory birds and associated species using the Cowichan Estuary which is a designated “Important Bird Area”.

CERCA jointly with Cowichan Tribes, Ducks Unlimited and FLNRO’s Vancouver Island Conservation Land Management Programme continue their efforts in restoring damaged salt marshes in the estuary.

Dr. Goetz Schuerholz

Chair CERCA